by sabriye tenberken

Today I would like to introduce an ambassador for a somewhat disreputable species: an advocate for insects, specifically, flies.

Flies are actually in dire need of an advocate. They have a truly bad reputation. Whenever there is news about an outbreak of diseases or a failed harvest, flies and grasshoppers often have their wings in the game. But still, I wonder: Can you really love such insects? I know many beekeepers and ant researchers who can quickly convince you how fascinating these little creatures are. But ambassadors for flies had not come my way until our 12th kanthari generation. Tobi Adegbite from Nigeria appeared, and many things changed: I rarely met someone who fell for the “big dark eyes” of the black soldier fly. He indeed raved about his flies, their rather hungry larvae, as well as the impressively large pupae, as if they were cuddly little puppies.

“You find them everywhere, especially in the tropics! Look here, how cute!” Enraptured, he held a handful of pupae in front of me, and his voice took on quite a gentle tone as he explained that it was now just a few more days before the flies would finally emerge.

At first, I could only take a humorous stance on the whole fly craze. But he remained persistent. Like a bull-terrier or better, like a soldier fly larva, he bit deep into the matter and slowly, very slowly his enthusiasm draped over us.

Adegbite Tobi Gabriel is a biologist and farmer from Nigeria. His passion for insects and especially for the black soldier fly has its origin in the many misfortunes he experienced as an active farmer. But he was not alone in this: worldwide, most farmers face major challenges, especially now, in times of climate change. Many are heavily in debt due to crop failures. There is little support, technical or financial.

But Tobi is also additionally concerned about the legacy of agriculture. One of the bigger problems he sees is organic waste, which rots and releases methane, one of the most devastating greenhouse gases. (Methane is about 30 times more harmful than CO2).

Another issue that had been on his mind since childhood was hunger. Tobi grew up in northern Nigeria. At that time, when he was only six years old, there was already a water shortage. His father often took him to the local government office to get drinking water. The water had to be carried home in buckets. This was the first time he came into contact with the World Health Organisation. The fact that many people in the world did not have enough to drink or eat was something that disturbed him greatly. He decided to get involved in the subject of food and so, after studying biology, he became a tenant farmer.

At first, he grew vegetables. But starting small was not his thing. With a team, he immediately farmed about 20 hectares and… The harvest failed, his team left and he was left with a mountain of debts.

He decided to put himself to the test again, this time in organic crop production and of course again on a very large scale on more than 30 hectares. However, this resulted in another hard landing, and the mountain of debts grew. It took a few years to pay off the debts, but hats off to Tobi, he wouldn’t give up.

And while he was confronted with all these failures, he was always looking for solutions, and, “bzzz-bzzz” the solution literally came flying at him in the form of a black soldier fly!

“A fly?” I wondered, somewhat disgusted, as we went through Tobi’s kanthari application. I had known flies until then only as an annoying and rather unappetizing cause of problems. “Since when are flies the solution?” Tobi later explained to me, that I should not make the mistake that all flies are the same! His black soldier flies would not have proboscises (mouth) and thus would not be interested in feeding on dung, on me, or on my food. The adult flies merely lay eggs. “It’s the larvae that do the real work!”

So, before we get back to our fly farmer, here are a few facts provided to me by his organization, Entojutu:

The entire life cycle of a black soldier fly lasts about 30 to 40 days. A female fly lays around 500 eggs on average. After about four days, the larvae hatch. Initially, a larva is not much bigger than a millimeter. But once it starts feeding, it is almost unstoppable and in 10 to 20 days it gains in weight and size and grows up to 25 millimeters long. Then it pupates and after three more days the transformation is complete. The food consists of organic waste. This includes meat and fish waste, something that does not belong at a composting plant and here has a lot of value. Once the larvae are full fed, they can also serve as protein-rich and very inexpensive feed for pigs, chickens, and fish. This saves on growing valuable grain or buying increasingly expensive commercial feed. And it’s a highly nutritious and healthy alternative, even for humans.

Are you already hooked?

Well, we here at the campus were all eager to see examples of the ‘magic tool’ highly promoted by Tobi in times of climate and food crisis. But the devil was in the details.

When the larvae pupated, we got a visit from a mongoose family. Stimulated by the promising titbits, they came in the dark morning hours to eat the whole brood, and then, a little later with full bellies past our office window in a victory parade.

The next generation didn’t last long either, because one of our overzealous colleagues thought the black creatures were somewhat unappetizing maggots, and “poof” the next crop ended up in the bio-gas tank. Tobi tried desperately to fish his “darlings” out of the foul-smelling sludge. But apart from a somewhat strong body odour and a few days of self-inflicted social isolation, the result was rather poor, and the experiment was abandoned.

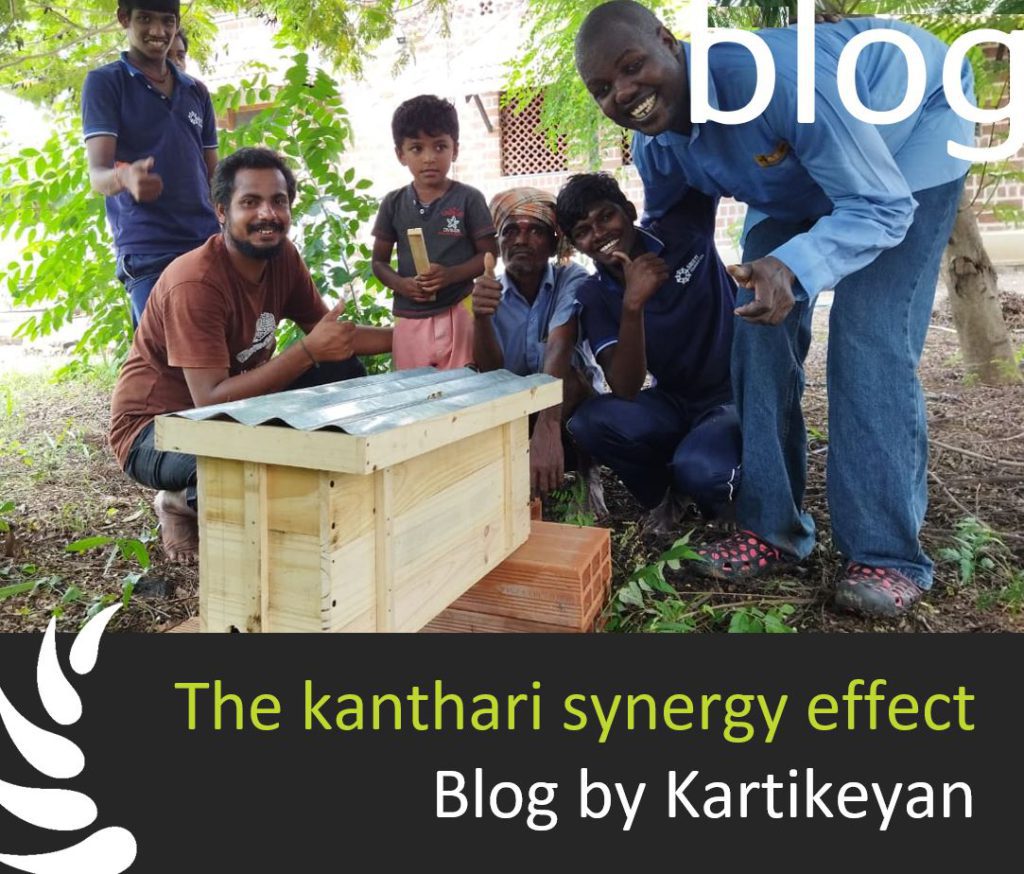

During the kanthari course, however, he was able to work with Paul to come up with a plan for a mobile insectarium. Unfortunately, we didn’t get to enjoy his inventions anymore. Before we could really implement it here on campus, he traveled back to Nigeria at the end of December and back to his team that, during his stay in Kerala, tried to raise black soldier flies in an old pig stable.

“And then it started!”, I heard Tobi sigh through the phone, “… I got one kick after another!”In a nutshell: Tobi had this “marvelous Idea” to pack all his precious papers and elaborate plans together with his birth certificate into his check-in luggage. But somewhere on the 23-hour flight, his suitcase got lost and it took Tobi two days of continuous pressure on the airport staff to get everything back.

In all this chaos, he forgot to take the compulsory Covid test. And when he finally wanted to travel home with his belongings, he was unceremoniously arrested by the local police and taken to court for not taking the Covid test. The judge fined him a significant amount. But where to get it from? His friends thought it was funny. Here you come from overseas and you don’t have any money? Fortunately, there were some merciful acquaintances who paid his fine. When he was finally free to take care of his flies, he caught Malaria and was sick in bed.

In the meantime, his teammates were fed up. Tobi was nowhere to be seen, they needed funds to survive, and the landlord who had provided the pig stable as a breeding ground for Tobi’s flies now wanted triple the price. Everything was in danger of falling apart. But Tobi’s mentor, Lawrence Afere, a kanthari from 2012 who runs Springboard (one of the largest organic farming training centres in Nigeria), came to the rescue: “Insects are indeed the future! You shouldn’t give up!” Lawrence, for his part, was experimenting with crickets and had promising results.

And then it really started for Tobi: Since the pig stable was no more, he made a fresh start by conducting an online course. Eight young farmers were enthusiastic about his ideas, the mobile insectarium, and are now putting this method into practice.

A project that works in East Africa and India, with the name Making More Health, has invited Tobi to Kenya to train 120 farmers. He had sent the designs of the mobile insectarium already to Kenya where these were already being constructed, in three different regions.

“And why are you not yet with your designs in Kenya?”, I ask Tobi. He whines theatrically. “Bureaucracy is tripping me up again! I need a new passport and the Nigerian government has run out of passport paper!”

You can’t really think of anything else to say, everything seems to be conspiring against Tobi. But when big ideas stumble over small obstacles, they are unlikely to break a leg.

PS. Last-minute update: good news! today, Tobi finally received his passport, so he is able to FLY again.