Summary

The Beer Hall Miracle (Norton, Zimbabwe) Part 2

Last February, paul and I, visited several kanthari graduates in Zimbabwe. In the same period, Chacko and Riya, our colleague catalysts, went to Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and Ruanda to meet kantharis there. What we saw and experienced was both shocking and encouraging. In the next few weeks, we will share blog posts that are a result of these journeys. Here is a chance to dive into African realities! Enjoy the read.

Today PART 2 of the beer hall miracle in Norton, Zimbabwe

(Read Part 1 here ) PART 2:

… When Nancy was only 16, she married a school headmaster. She laughed when she told me about her choice. “I believed he was my ticket to more education. But that hope remained unfulfilled!” Soon enough she had two children in quick succession and adopted four more children from a deceased relative.

“I think it became too much for my husband at the time. He started abusing me and eventually, he threw me out on the street with the little belongings I had and with my six children. And there I was again, looking for food every day. Whenever I had money left, I sent the children to school. We were all malnourished and had no soap and no clean water to wash. My clothes were torn, and my hair stood wildly in all directions.” She giggles with amusement, “Haha! The people called me a mad woman!” But then she became serious again. “We all had skin problems, my children got ring worms and the teacher didn’t want them to come to school anymore, they could have infected their classmates.”

There was a time when Nancy started looking for ways to take her own life. But then the long hoped-for turnaround finally came: She found a donor who donated a scholarship to all her children. And with that, everything changed for her and slowly she was able to determine her own life again. The question here is how many problems could be eliminated if only the government would realise that primary and secondary education of children and youth should be the responsibility of the state. In India, public schools are also government affairs, and the children even get free and substantial lunches. So, once school fees are out of the way here in Zimbabwe, parents would only have to pay for the expensive textbooks and uniforms. And there again, I believe that uniforms and books should be the responsibility of the state. After all, uniforms are compulsory, and don’t soldiers also get their uniforms provided by the government? And what is the family’s responsibility then? Nancy asks me very attentively. “Healthy and regular food, a clean and child-friendly environment, and a loving and violence-free home.” Nancy agrees. But as logical as the whole thing may sound, the reality is very far from this utopia. Here in her school, Nancy tries everything to create as much justice as possible. The teachers turn a blind eye if the children don’t come in uniforms and books are either shared by at least five children or there are simply no books.

Teaching without books is not easy for the teachers, however, after many discussions about alternative education at kanthari, Nancy also sees a possible opportunity in this.

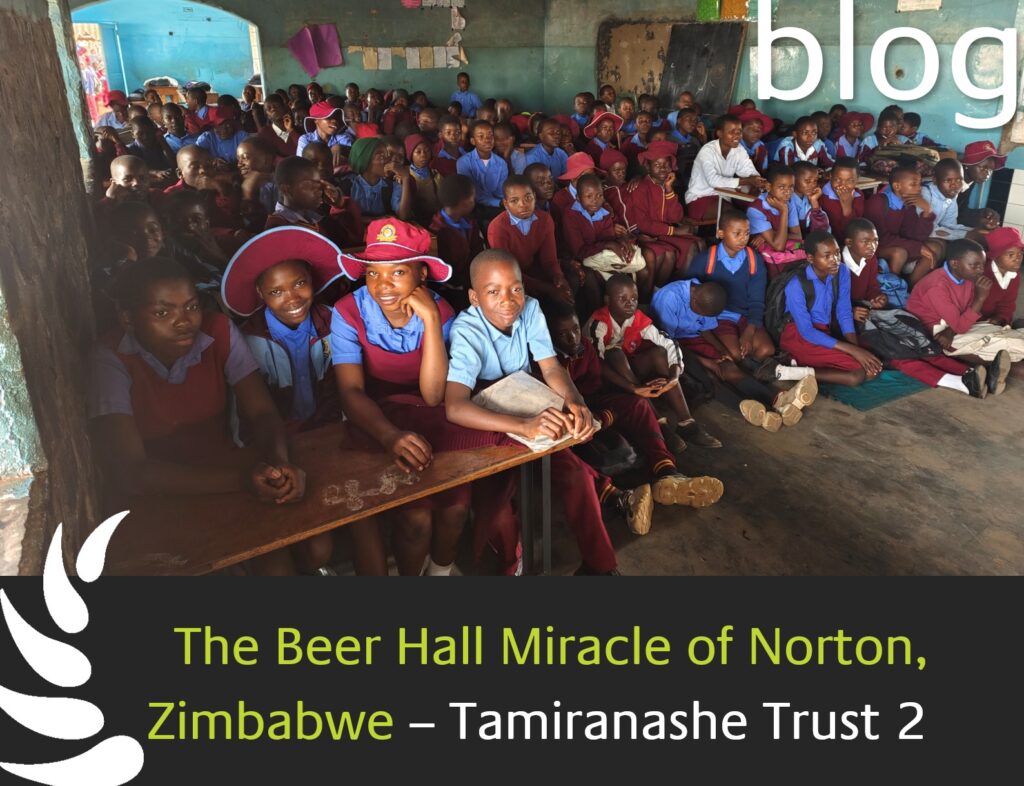

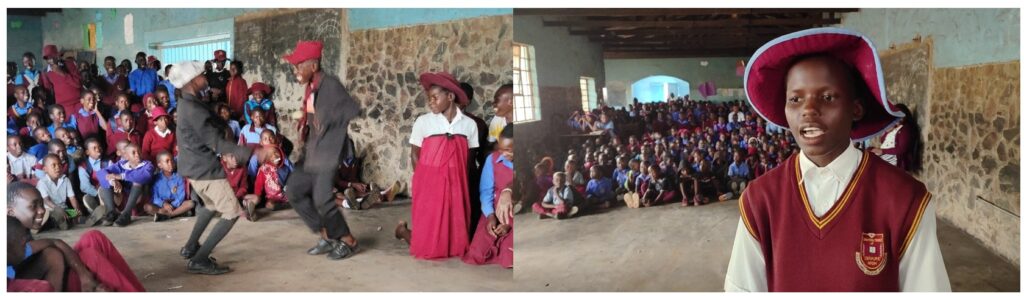

She wants the teachers to think of their own means to make the lessons as creative as possible. And apparently, this seems to be working. The teachers now feel free to choose their own methods. They bring their own interests into the lessons and want to create a lively classroom atmosphere. Since there are no blackboards, they cannot teach in a frontal manner. They have to involve the children and the result was stunning. One day before our visit, Nancy had announced to the students that they should enlighten us in some creative way about their lives, their fears, and desires. We were a little wary because in the morning we were channeled through all the classes and greeted with almost military-like slogans from at least 50 children’s throats in complete synchrony. But then we sat in a hall, in front of us about seven hundred children aged between 4 and 13, and for several hours we were presented with a specially compiled, very entertaining programme.

Everything started with a very rhythmic and polyphonic choir singing songs that were composed by the children themselves, which left us completely speechless with amazement. I have rarely heard anything so touching from children’s choirs. The singers, aged 11 to 13, not only had incredible verve, but they were also simply professional through and through. Nancy was also thrilled. She didn’t know the songs but translated the short and rather disturbing lyrics of one song for me. When the father drinks wine in the evening, everything goes haywire. The distress that spoke in this text would not have been noticeable at all in the lively choir.

But then things got serious, or rather visibly and audibly angry. Brenda Benjamin, a 12-year-old student of Grade 6 recited her poem about “The Girl-child”. It was about the fate of girls who first see the light of day unwanted. Then they are always second choice throughout their childhood, they get less to eat than their brothers, have to help out in the household from an early age, are not allowed to play, not allowed to be children, they only can go to school as long as the school fees are enough for the boys too. But then they have to prepare themselves for life as a wife and mother. At 13, they are ready. Marriage is contracted and the girls mutate into adult slaves practically overnight. Well, they were slaves before, but now they belong to someone else’s household and if everything doesn’t work out to their satisfaction, there will be beatings and rape. The children born to mothers who are still children themselves don’t make the situation any better. “It is already a damned fate to be a girl!” she exclaims in conclusion, “but I will break the cycle and do everything differently. I will fight for my rights!”

There is great applause and the women who were invited as guests, like us, are happy about the clear words and the courage to finally address something that most of them had experienced themselves. Some inter-generational children’s groups had prepared little plays for us. The children were either excellent actors or, and this was Nancy’s opinion, they were simply acting out what they witnessed every day at home and in their environment. And although they clearly enjoyed the theatre, the content of the plays was rather depressing. In particular, it was about alcohol and drug abuse, an issue that is considered one of the biggest social problems here in Zimbabwe.

Already in the morning, we were confronted with the topic in our interviews. “We worry all the time,” said a grandmother who has one of her grandsons in school. “The drug dealers are everywhere. They wait for our children when they come from school, and they tempt them by giving them little gifts.”

What kind of drugs are we talking about? Paul asked. “Everything”, said the teacher, who was partly acting as a translator. “especially crystal meth!

“And where do they get the money? How can children afford such expensive drugs when already 7 US dollars for school fees cannot be raised?”

“They steal, mainly from their own family. The school fees are the first to go.”

This is exactly what the children acted out in a very credible manner. Paul later said that it was very shocking to see how well they could imitate pulling on a joint while others very convincingly acted out their drunken and drugged fathers who took the little money intended for the daily meal to the beer hall right after work. It was fortunate that at least Nancy’s beer hall had closed the ever-running tap.

At the end, there was a theatre play that left me thinking for a long time. It was about faith. Superstition and church faith were more or less equated, or better, juxtaposed. There was a problem with stolen money. The victim, a boy, didn’t know what to do and first went to a “N’anga”, the local traditional healer or witch. But he only wanted more money to catch the thief. And if the boy was not able to pay, he would bewitch him. Discouraged by this unscrupulous attempt at blackmail, the boy now went to the Apostolic Church, the White Garment sect, but here, too, unfair conditions were imposed. They would only help the victim if he joined the church and served the superiors.

I had the feeling that this play touched on a fundamental problem, responsible for many ensuing crises and social hardships. So here were two influential giants facing each other: the omnipresent superstition of witchcraft and the dangerous fanatical belief in God. Both forces abuse their power.

“And who wins?” I asked Nancy, who was sitting next to me, translating the play in broad strokes. “Neither of them! Not the witch and not the church either! The winner is the one who understands that we have to rely only on ourselves, on our own minds!”

Learn more about the inspiring work of Nancy at https://tamiranashetrust.org/