Summary

The Beer Hall Miracle (Norton, Zimbabwe) Part 1

Last February, paul and I, visited several kanthari graduates in Zimbabwe. In the same period, Chacko and Riya, our colleague catalysts, went to Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and Ruanda to meet kantharis there. What we saw and experienced was both shocking and encouraging. In the next few weeks, we will share blog posts that are a result of these journeys.

Here is a chance to dive into African realities! Enjoy the read.

by Sabriye Tenberken

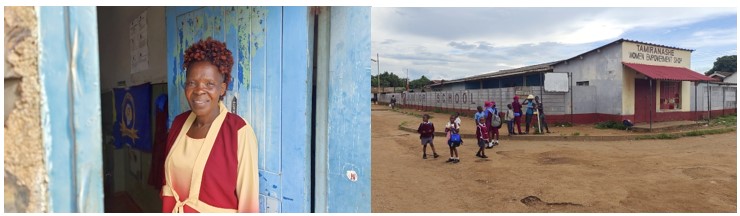

“When the quest for knowledge tramples poverty, then Zimbabwe can change for the better.” Says Nancy Mbaura, and she not only says it, but she also acts accordingly. About seven years ago, in 2016, she and single mothers ensured that a beer hall located in the centre of the small town of Norton was converted into a primary school. That sounds easier than it is. Because the drunkards didn’t appreciate being pushed out of their comfort zone. They protested and tried to boycott the project. They almost managed to stir up local politicians against Nancy and her team.

“Every day, district officials and police officers came and insulted me in front of our students and staff. It was so embarrassing. It was like being accused of murder.”

Paul and I know similar situations all too well. In Tibet, we too were regularly insulted and treated like criminals in front of our children by neighbours or even official authorities, and we were often on the verge of dropping everything, had it not been for the blind students who needed us and a school. The children of Norton also needed an advocate, someone like Nancy. Education has proven to be the only way out of poverty here. And Nancy and her “gang of women” had indeed managed to fight against all obstacles.

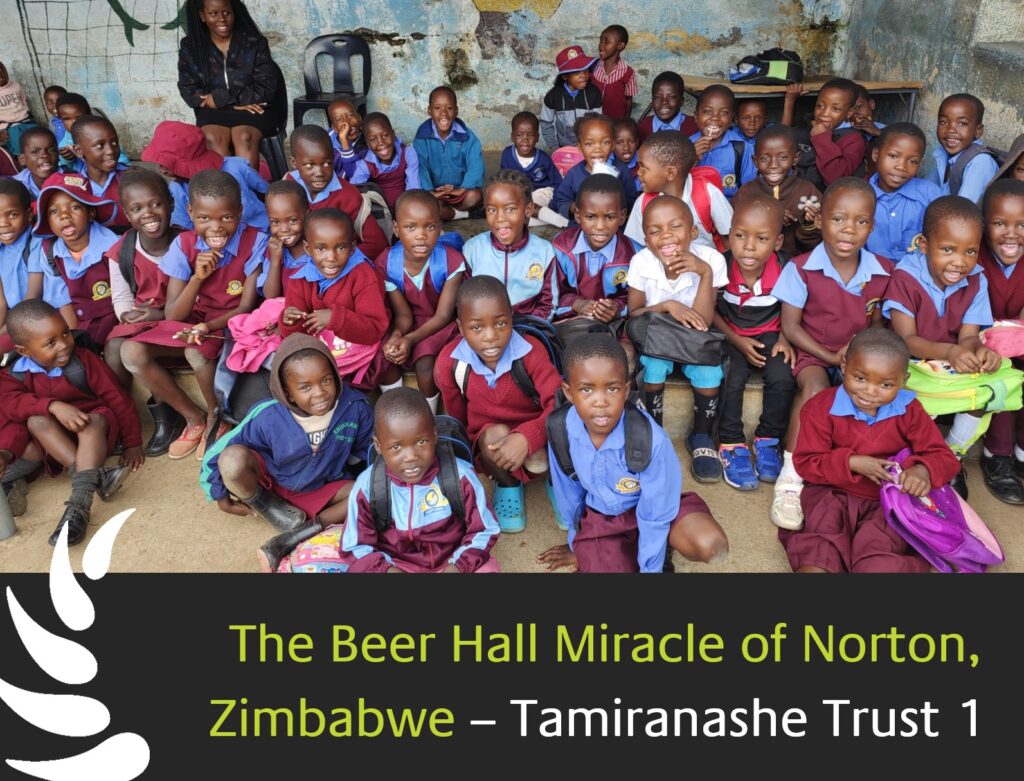

Today, the primary school has more than 900 children and its recently opened secondary school has over 800 more students.

Nancy Mbaura, a Norton veteran and a highly committed kanthari participant of the 2022 generation, had to fight for her right to education as a child. Her parents were poor and could only afford the necessary school fees for her and her three younger siblings on an irregular basis. Nancy writes about her own childhood: “At the age of seven, I was often sent home by the teachers because the school fees were once again not paid. Then, when I was home alone, a neighbour took advantage of the situation and brutally raped me. From that day on, I realised something crucial: School is not only a place of learning but also a place of refuge.

The former beer hall now offers such a refuge for the otherwise neglected children of Norton. In our interviews with concerned parents, we heard one point over and over again:

“We know that our children are in good hands here. The teachers care and always have an open ear for us parents and every student. That’s not the case everywhere. Public schools would charge a fee for every extra tutoring hour.”

Emily, a dedicated grandmother beamed as she talked about the school and the teachers: “Even though everyone makes fun of our school when they say, >What’s that?! Just a simple beerhall!> Well, we are happy that this school exists at all. Of course, people here are quite arrogant…,” she then adds. If only the school looked a bit more like a private school, with a bit of paint, proper partitions, a blackboard in every classroom and maybe even chairs for the children to sit on, then they would no longer say, >Oh, this is the poor people’s school<, then they would understand that our children get good classes here and that we only have to pay a small fee for valuable education.”

One of the most serious problems in Zimbabwe is that parents, rich or poor, have to pay school fees for every child. According to the government, however, attendance at public schools is officially free of charge. But how to cash in anyway, without incurring the direct wrath of the population? Well, the politicians have come up with the cunning idea of simply forking out a handsome “donation” for the “development of educational institutions”.

The compulsory amount of US$ 20 or more per month, per student, should support all extras like sports facilities, musical instruments, and art materials. The question is, where are these extras? Where all the money goes, nobody asks anymore. They just shrug their shoulders and laugh out loud.

But the many people who live below the poverty line have nothing to laugh about. For a family that has to get by on no more than 100 dollars a month, 20 dollars means a pretty hard cut in the household budget. And most families, especially the poor ones, don’t have just one child. Three children are still few. In addition, many women are single

parents and there are a large number of so-called “child-headed families”, i.e. families that have to be fed by the eldest brother or sister.

The “child-headed family” is a rather rare phenomenon in Europe but also Kerala. If, for example, a family with underaged children in Germany or southern India loses its parents and has no other relatives who can take care of them, the state immediately steps in and takes over guardianship. In Zimbabwe, state care does exist, too, but only on paper. The reality was and is still different.

When Nancy turned 12, everything for her and her younger siblings turned upside down. The father, who had been temporarily employed in a factory, had embezzled funds, and went to jail for a year. “I know he had done it to secure us”, Nancy explains, without a hint of bitterness. “But my mother was so dependent on my father that she suffered a breakdown. Her relatives worried about her and took her away from us. We children were now on our own. And so, I became the mother of my siblings at a very young age.”

Nancy had to make sure they had enough to eat and had warm clothes; school was out of the question. The children stole vegetables from the market or helped themselves to edible scraps. But at some point, the neighbours complained and called an aunt to take them to a tobacco farm far away. The farm owner, a white man, shamelessly exploited the children’s misery. For hours every day, under the burning sun, he made them remove worms from tobacco leaves. He pretended to be “generous”, by offering them either little pay for a lot of hard work or, instead of a “salary” they could gain basic education, in the farm’s own primary school. While her younger siblings preferred to work for money, Nancy chose education, however miserable it was. There was only one teacher who didn’t know much more than she did, he was responsible for seven grades at a time. “I didn’t mind because I just wanted to learn. Somehow, I knew even then that only education would get me out of the prison of poverty. And yet, there was still a long way to go before I could finally take my life into my own hands.”

Sadly, the experiences Nancy and her siblings had to go through many years ago are still a bitter reality today. In front of us were a few of the many children who come from “Child-headed Families”. A 14-year-old boy who looks a bit shyly into the camera does not know exactly why he was called to talk to us.

The teacher asked him to tell us something about his family circumstances. Somewhat embarrassed, he described the conditions at home in Shona. The parents are no longer alive. We don’t know why. His older brother takes care of him and his little sister. The brother does not go to school, says the boy when asked, although he should, because the brother who takes care of clothes, school uniforms, food, washing, and medical needs of the younger siblings every day is only 15 years old. Fortunately, at the Tamiranashe School, the children only pay seven US dollars each per month in school fees. That is comparatively little. But still too much for such a family.

We are sitting in the office of the headmistress of the Tamiranashe Trust, which is founded and run by Nancy. The trust takes care of all the school’s needs and the needs of the single women. Training courses in truck driving, or administration of micro-enterprises are available. To generate income, one of the buildings in the school compound is used as a shop. It has a window at the street side through which several home-made products are sold: fruit juice, that is made with a machine that was donated by my uncle, and several baked goods. But these days, Nancy is particularly concerned about the needs of the children.

She has the ambition to create a school with few resources that is known for offering excellent teaching to the children on the one hand, but on the other hand, should not exclude anyone. “Everyone is welcome here” says Nancy with great confidence that perhaps borders a little on hubris. “We are open for all kinds of disabled children, pregnant teenage girls and children from desperately poor families!” In fact, Tamiranashe was particularly notable for being the only school not to charge fees for years. But this year, for the first time, Nancy was forced to introduce a small school fee, extremely low for Zimbabwe. “Otherwise, I wouldn’t have been able to keep my teachers.”

The dedicated teachers currently receive approximately only 100 US dollars a month, even though they have to teach two classes of 50 to 70 pupils a day. They make long hours and because of that, as is the case for most other Zimbabweans, lack the time for a second job.

But when the bad news was given to the parents, a third of the children promptly stopped coming to class. “Not in protest,” the headmistress said sadly, “they just couldn’t afford it.”

“We pay off dollar after dollar every week, but I don’t know how much longer I can pay,” said one mother in an interview with us. Another one was eager to talk to us as well. Like many other mothers, she was single and had seven school-aged children to support. She had only two of her children in primary school. The youngest, a four-year-old child, she carried in her arms. She had come to ask Nancy to admit her youngest to the Tamiranashe preschool free of charge. Because if the little boy was no longer hanging on her coattail, she would have the opportunity to pick Sadza out of the leftover food in the restaurants and cookshops. She would then sell this to the fishermen at the nearby lake for a few Zim-dollars as bait. Again, a diabolical chain reaction. She has to take care of the toddler as he cannot be admitted without school fees. As a result, she has no time to generate income and is unable to provide for the welfare of her children.

Many marry far too early in this area. Doing so, they hope to be able to catapult themselves out of the poverty cycle, but do not realise that by having children too early they only put themselves deeper into dependency. Often the women experience violence and if they then find the courage to separate, they live in abject poverty and have to take care of all the children alone….

Next week you can read more about Nancy’s personal journey and the work of Tamiranashe… Stay tuned.

More information about Nancy’s work can be found on https://tamiranashetrust.org/