Summary

In the backyard of an isolated uncompleted building, a hideout in one neighborhood in Bamenda, Cameroon, groups of youth can be seen smoking marijuana and sniffing cocaine in turns. This is a rather common scene… Cameroon’s anti-national drug committee indicates that 60% of young people between 15-25 have been users of traditional drugs such as alcohol, local gin, imported cocaine, and/or amphetamine tablets that come from transit countries like Nigeria or Ivory Coast. War-prone countries have a higher rate of drug consumption, and youth are lured into drug use by separatist fighters.

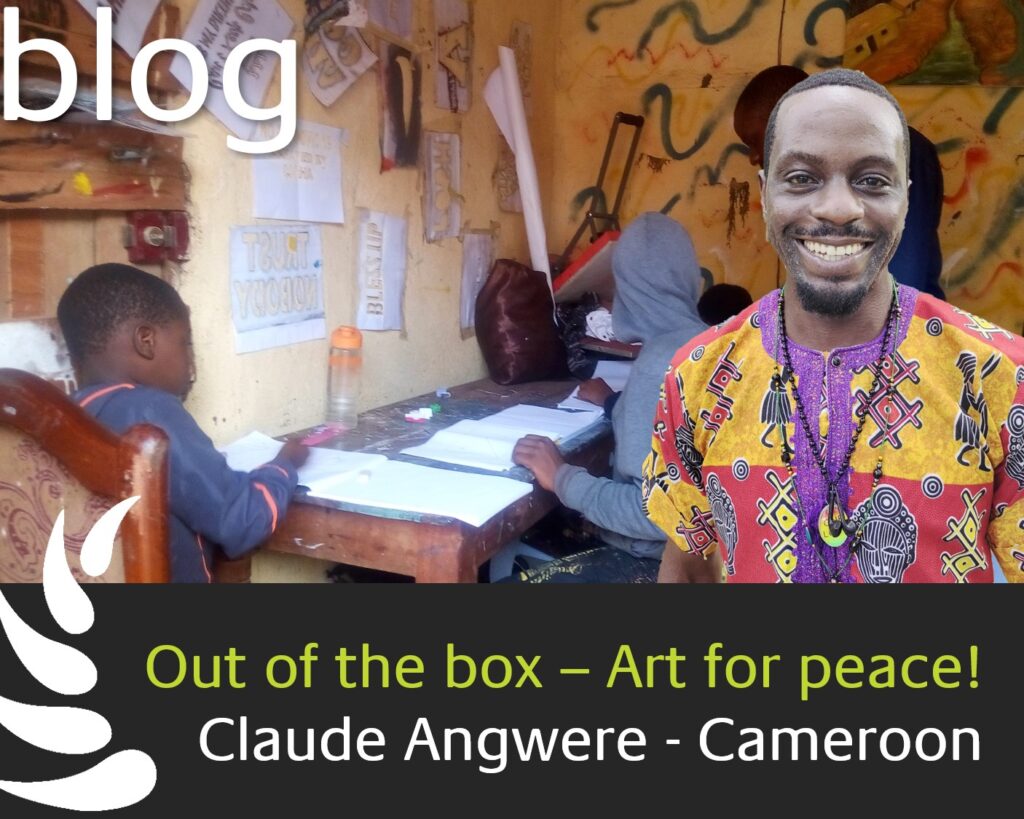

Because of a brutal civil war, the artist Claude Angwere has experienced drug abuse like many youths in north-west Cameroon, being side-lined or lured into political activities.

Claude wants to work with drug users and former child soldiers. By engaging them in art activities, he wants to organize the first African biennale to bring a change to a war-torn country.

– By Claude Angwere

Imagine a miniature Biennale, an inner-city outdoor exhibition, covering dark corners, tree trunks, and junctions with paintings and sculptures. Imagine a city that wakes up to the sounds of street theatre and traditional music, with video walls that show short art films and documentaries! These are activities that will be conducted every two years by artists, my beneficiaries who leave their life of daily drug use behind and find their way back to a life of purpose. We might have been lost souls, but now we are back to bringing beauty and value to a city that was taken hostage by violence and poverty.

I was born in 1982 into an average middle-class family, a twin and the only boy to my mother. My mother and sisters treated me like a prince, we went to one of the best schools, and I had fancy clothes, and all I could wish for. But the protective childhood was soon over.

The first multi-party presidential elections in Cameroon in the early nineties were characterized by rigging and fraud, leading to political instabilities and civil strife in several regions, including the Northwest region of Cameroon. The Government declared a state of emergency, and opposition activists, demonstrators, and civilians were killed or arrested. The opposition called for ghost towns, the closing of shops, businesses, taxi services, schools, and refusal to pay taxes among others.

At the age of 11, I was lured to an activist camp where I stayed for about two years. The activists forced us to use drugs to make us immune to anti-social actions. My job was to be a spy. Neither my mother nor any family member knew where I was.

Luckily, one day I was able to return home. I went back to school but failed my examinations, so I dropped out of college and continued to use drugs. I remember one evening, after having excessively consumed alcohol and marijuana, I fought with my mother and sister. My belongings were thrown out of the house. I had no choice but to gather my belongings and live on the streets.

In 2003, my mother, now a single parent, asked some friends to bring me back home. She believed I was bewitched and took me to a psychiatrist for mental counselling and later to several churches. Now I know that prayers didn’t help me. My mother was the major force in getting me on my path, and I learned that I had to heal myself.

My mother insisted that I go back to school and successfully graduated. After that, I enrolled in Fine arts, Theatre-Production, and Cinematography at a University in Yaounde, the capital city, in the francophone part of our country.

As a native English speaker, I experienced repression and marginalization from my French brothers firsthand. It was reflected in the educational, social, administrative, and economic strata. Thus, after my degree, I immediately returned to the North-west region. My mother’s attempts to send me to study or to travel abroad failed, and I always blamed my government. I gradually saw myself returning to my old way of life, using drugs, and becoming economically dependent on my family again.

Back to square one and to my passion for creating art, I asked a local carpenter to create a one-square metre square wooden box. I positioned the box on the side of the street, and it became my art office and workshop. I started drawing, painting portraits, printing T-shirts, and creating rubber stamps for commercial use. When I was making some money, I offered training opportunities for youngsters who have similar life stories. My mother understood that I found my path and supported me so I could rent a better workshop, this time a plastered, painted room.

This is where I am today, trying to change the lives of those who are victims of political and social hazards. And maybe, there will be one day when my home city honors those who were always outsiders as the ones who contribute a little beauty to a city that has been shaken by struggles.