by Sabriye Tenberken

Many kanthari graduates who have managed to overcome the first hurdles, feel just like we did back in our early years in Tibet. Even when we have clarity in our direction and successfully overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles, sooner or later we all fall into a hole that is difficult to get out of. We feel alone and perhaps a little out of place because being a kanthari often means approaching problems in a way that others may not agree with or understand.

If you don’t belong to a network of similarly functioning/thinking founders who encourage each other carry on, then it could result in giving up even before the project has really started.

When Paul and I were starting our journey back in Tibet, we were lucky to have close contact with a rather small expatriate community that consisted of French, Belgian, Italian, and English delegates who worked for aid organizations that were based in Lhasa.

In times of crises when donations were scarce and we could not properly clothe our blind children for the winter, they helped us out quickly and unbureaucratically. Paul would reciprocate by sharing his technical know-how: hooking up the first internet connections and making designs for village clinics/offices. Together, we celebrated birthdays, Halloween, and those who were brave enough to stay during the long cold winters, met in one of the NGO headquarters, huddled around small electric stoves and preparing something like a pizza or a pasta dish made from available local ingredients..

Despite the many friendships, what we lacked, however, were like-minded people. The ex-pats were mostly delegates from Medicines sans Frontières or Save the children, but rarely the founders of the organisations themselves. We longed for contact with people who, like us, were “crazy” enough to set up a school, or a clinic.

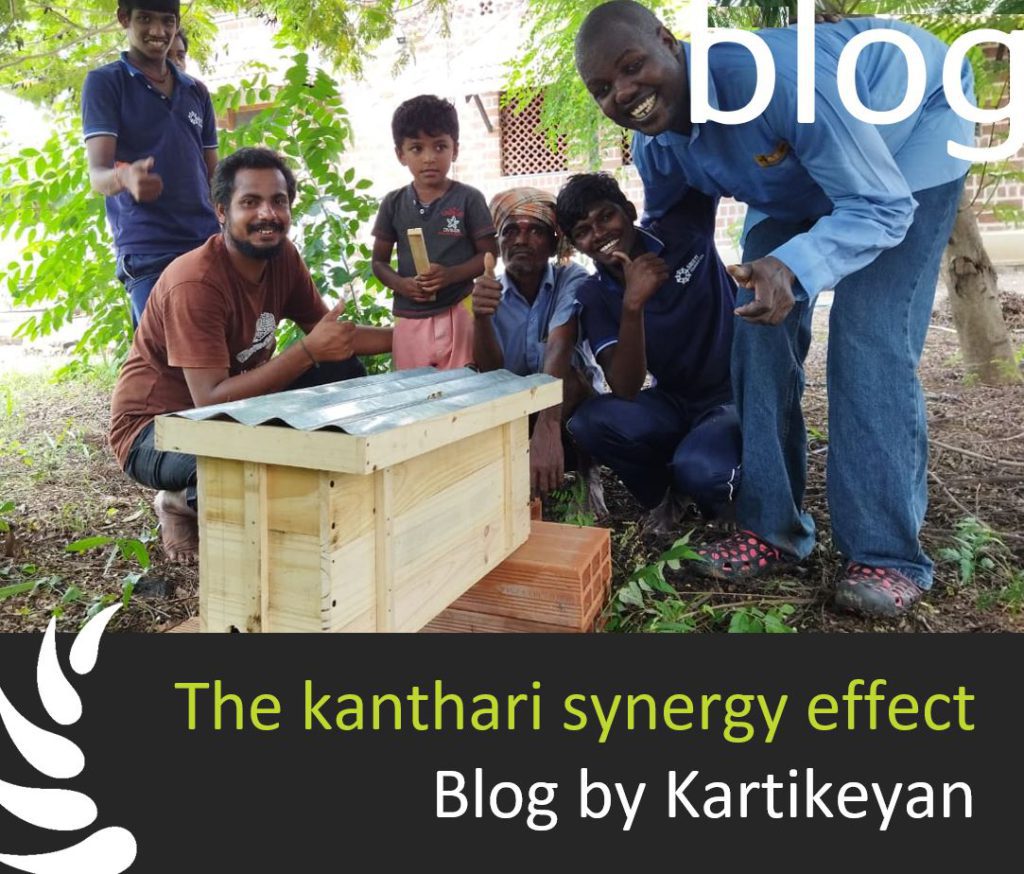

A delegate from an aid organization usually “only” implements the aid measures devised and fundraised in faraway Europe, and due to extensive red tape, obsolete at the time of implementation.In contrast a founder is solely responsible for all that encompasses their project. Today we are sure that our graduates with their local kanthari network will fare better, and we welcome any signs of intergenerational solidarity. Those who come from countries where many kantharis are already working have a special advantage. While friends or family members tend to be skeptical about new, often very unconventional project ideas, kantharis always have an open ear and since they know the bureaucratic processes, the possibilities, but also the limits of their own country firsthand, they can assist the “starters” with practical solutions.

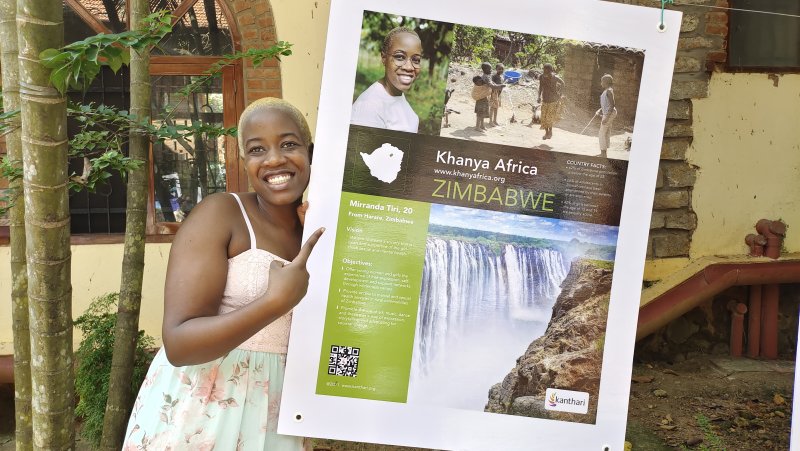

A good example of a solidarity network among kantharis is Zimbabwe. Mirranda’s reports make it clear how important such intergenerational support can be in the initial phase.

Mirranda returned to Zimbabwe about three months ago. Last week we caught up on a phone call:

“Hello?”

“Hi!”

“Can you hear me?”

The ever-present network issues never hold us back from having regular exchanges with the kanthari alumni. And this week it’s Mirranda’s turn.

Being 20 years of age, she was one of the youngest kanthari participants. Officially, we only accept applications from change-makers who are 22 or older as a significant portion of life experience forms a proper foundation. But when looking through Mirranda’s application and CV, the minimum age became irrelevant.

During the months Mirranda was here on campus, I met with her on our rooftop terrace and listened to her life story. I was shocked, amazed, and full of admiration. What Mirranda went through in just two decades could easily fill three lifetimes! She was only six years old when her mother could no longer stand her violent alcoholic husband. Her mum left the children with their father to start a new life in South Africa.

From then on, Mirranda and her two-year older sister became involuntary nomads. They were moved from one family to the next, and wherever they went, they felt like they did not belong; they were either being taken advantage of, or they were a burden. Mirranda spoke about daily verbal violence, rejection, and being raped by one of her more distant cousins. The cousin threatened her with the words: “Ukangotaura chete ndinokuuraya nemhuri yako” (If you tell anyone, I will kill you and your family).

Right at the beginning of the course, when all participants introduce themselves, Mirranda, for the first time shared this traumatic experience, a bit shaken and with a trembling voice. During our meeting on the roof terrace, which took place almost three months later, she again described this part of her life, this time without shame, but with a good portion of rage. She made it clear to me that she no longer wanted to hide it. She made her experience public through social media without mentioning the name of the cousin. This caused somewhat of a family crisis.

“He can’t kill me anymore because the little helpless girl from that time is already dead.Instead, I am alive! I am strong, and I know how to fight back.”

Her strength and message can be clearly heard in her dream speech at kanthariTALKS. She is a true survivor. Strong, but not bitter, she tells of dark, heartbroken times, but also of beautiful experiences. When she was about 9 years old, her mother came back to her and her sister. The mother had fallen in love with a German resident and for the first time, though only for a few years, the two children experienced what it meant to be part of a loving and caring family.

The new stepfather had a dream. He wanted to set up an eco-tourism camp in Namibia. The wilderness, the lake, the hippos, and the nightly campfires under the starry sky was their home for a whole five years. But then her mother became seriously ill. She was brought back to Zimbabwe where she passed away. Mirranda was only 14 years old.

“From then on, we again moved from one household to the other. Every now and then I lived in a boarding school. But everywhere I felt lonely.”

At some point, the siblings hatched a plan. They wanted to go back to Namibia, back to their stepfather. But when they contacted him, they discovered that he had died by suicide. He couldn’t bear the thought of living without Mirranda’s mom.

“In the end, we had to live with our grandfather. But he soon got fed up too and chased us away. That was a blessing in disguise because now we could officially take care of ourselves. My sister and I rented a room and for the first time in our lives we had a home!”

And where did all her experiences lead to? In her kanthariTALK, Mirranda describes her dream project called “Khanya Africa”, an organisation that addresses teenagers who have faced challenges like herself. She wants to encourage teenage girls to seek help in case they feel down or lonely. Either through professional support, or by reaching out to Khanya Africa.

To renew their motivation and self-confidence, she will organize workshops and wilderness camps. She wants many teenagers to have positive experiences with the wilderness as she and her sister had back in Namibia.

A German friend of mine, a father of two teenagers, saw her kanthari talk in the livestream. His 17 year old son, who was going through a motivational crisis, was so impressed by Mirranda’s self-confidence, willpower, and openness that he was going to do a paper on Mirranda and her life for his school.

And what has Mirranda been doing since she returned to Zimbabwe?

At the beginning of this year, she organized her first Khanya workshop with 14 girls between the ages of 9 and 20.

Many of the young girls shared about their emotions, their fears of not being loved, of their worries about the future, but also of their hopes of finding suitable solutions for their problems.

Ruvimba (name changed), 18 years old, for the first time in her life, shared about the sexual abuse she had experienced. And just like Mirranda, she does not want to be a victim but wants to help other children to fight back. “She will definitely apply for kanthari one day.” says Mirranda, and I can hear how happy she is to be able to be a link in the kanthari chain.

Mirranda herself learned about the kanthari program from Trevor, a 2018 graduate who works for the oppressed and stigmatized LGBTQ community in Zimbabwe through his organization Purple Hand Africa. Together they contacted Nancy, a dedicated school initiator, and selected participant in this year’s kanthari course. To hold her first Khanya Africa workshop, Nancy offered Mirranda space in her school. Do you see how empowering a like-minded network can be?!

This is how information about kanthari is passed on from one generation to the next. Slowly a web of committed change-makers, project founders, and initiators is being spun into a strong community that we so desperately needed back in our early days in Tibet!